Last week, AI-controlled cameras at a Scottish Championship game between ICT and Ayr mistook the linesman’s bald head for the ball, and tracked it for several minutes -- you have to see this.

Obviously, my first thought upon seeing this was of the complex, part-bioinformatic, part-financial intersection between football (soccer, fine) and technology (you mean yours wasn’t?).

Football has cost me a broken arm (4th grade - I wasn’t in great shape, and I landed awkwardly, OK?), countless hours of sleep (I witnessed many a Singaporean sunrise watching my beloved Tottenham play random Eastern European teams on Thursdays), and more recently, more subscription money than I’d care to admit (the broadcasting landscape here in the US is, well, criminally fragmented), but I am trapped in a relationship with it all the same.

So, here goes one of the most self-indulgent pieces I’ll ever write -- one about the role of technology in sharpening the performance, integrity and consumption of the beautiful game.

In setting the scene, it’s important to understand how notable it is that football is allowing itself to be disrupted at all. Priding itself on its many vintages of notorious hardmen, on its conceptual simplicity, and on rewarding passion as much as overly intricate tactics, football long lagged behind its ever-modernizing peers -- while game film, wearable devices and sabermetrics ate up other blockbuster sports, football remained blissfully traditional.

But as the stakes changed, this was never going to last. In the past decade, we’ve witnessed the transition of football from a sport into a network of full-fledged corporate structures.

Accordingly, today, football clubs are being scrutinized almost like private equity opportunities, acquired not for their sporting heritage but for their brand names, merchandising, TV rights, stadia, players (as multi-million dollar assets, not cultural icons) and global reach, with their owners ranging from Chinese holding corporations (Inter Milan) to media consortia (Sunderland) to Russian oil tycoons (too many to list).

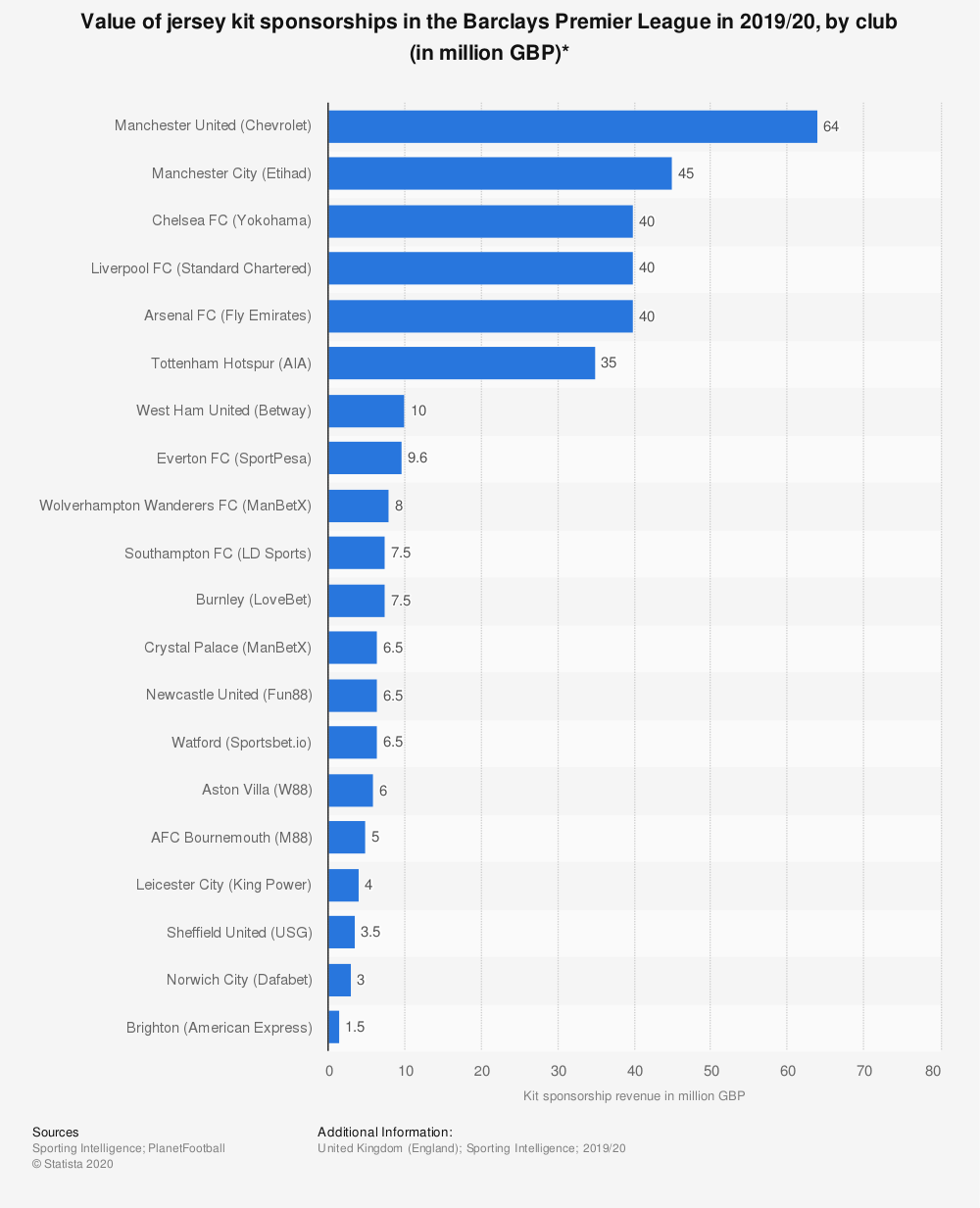

Jerseys are no longer merely baggy and made for muddying -- they are form-fitting, sponsored (the graphic below shows just how lucrative these deals are), Nike-made commodities, whose international sales potential often dictates (and even pays the wages of) the players that are signed to play in them.

Even the leagues that football clubs play in are being corporatized and then restructured for returns on investable assets. Italy’s Serie A, for example, recently spun off its broadcasting rights into its own legal entity -- the 10% stake that private equity investors like Bain Capital and CVC are pondering is valued at up to 1.6 billion euros.

In fact, as was explained to me in a recent conversation about it, this Serie A opportunity is being diligenced with a pretty textbook private equity value creation lens. In other words, questions like:

How do we get Juventus, Napoli and Lazio onto as many TV screens as possible?

How do we make the coverage better, and

How do we maximize our paycheck when we leave?

All this is to say that the ‘game’ itself is getting further and further away from the pitch, and somewhat paradoxically, that makes what happens on the pitch -- who wins, and how people experience it -- all the more important.

So, like in every stubborn industry from insurance to retail, enter technology to provide the edge.

Performance

The first edge that technology provides is in optimizing performance -- novel algorithms, sensor/software combinations and devices are furnishing football clubs with analytical gains they can use to put matchday smiles on the faces of their investors (***fans, I meant fans).

Once again, it is something of a paradox that every single one of these gains is made before -- often, long before -- the ninety minutes in which a match is played. A brawny sport is increasingly being won in advance with the brain. In abstractly chronological order within the lifecycle of a single football match, here’s how:

The summer before the match:

Transfer windows vary from league to league, but typically, the two periods of time in which a club can sign a player from another are the summer (May-August) and the winter (January). Like a private market but more emotional, transfer windows see a combination of patient, timely, long-negotiated signings of some players, and the frantic, arm-twisting deadline-day signings of others -- often resulting in clubs either paying over the odds, or scoring absolute steals from clubs in need of quick liquidity after their own spending.

It is dramatic and beautiful.

The process of scouting underscores and informs this chaos. Throughout the year, clubs send a network of scouts around the world to watch, study, meet and learn about players. These scouts in turn produce evaluative reports about these players as potential signings for their club, covering everything from tactical compatibility to personality.

Given what’s at stake now that players have become multi-million dollar commodities, clubs are rapidly expanding their scouting networks, and each scout is under pressure to relay more comprehensive insights than ever. And this creates a processing problem.

The legacy method of processing scouting reports was simply to use, well, other scouts -- they would sit at the club’s HQ, parsing qualitatively through reports to see if they happened to spot someone worth more attention. With today’s increased scouting dataflow, depth-wise and width-wise, this method would spawn massive data bottlenecks.

In other words, without efficient and holistic processing, there is no useful upside to scouting -- the only such upside being to get a new gem, hidden or otherwise, onto the pitch. That’s without even considering the downside of scouting, which is exacerbated by the public nature of football -- forget being the guy who said Messi was too small, who wants to be the guy who lost Messi’s scouting report in a paper pile?

As always, though, there is hope for the brave. Just Add AI’s IBM-powered JAAI SCOUT is one example of a product that can revolutionize the recruiting process, if traditionalists are willing to let it.

The premise is straightforward. Actual scouting data -- the stuff that comes back in the files from far away lands -- is unstructured and qualitative. Full of useful insights across the gamut of sporting traits, as aforementioned, these reports are indispensable in corroborating hypotheses and hunches that are formed about players. Dissatisfied with the order of events, though, JAAI set about trying to help clubs form those hypotheses in the first place by pulling them elegantly from the data already at their disposal.

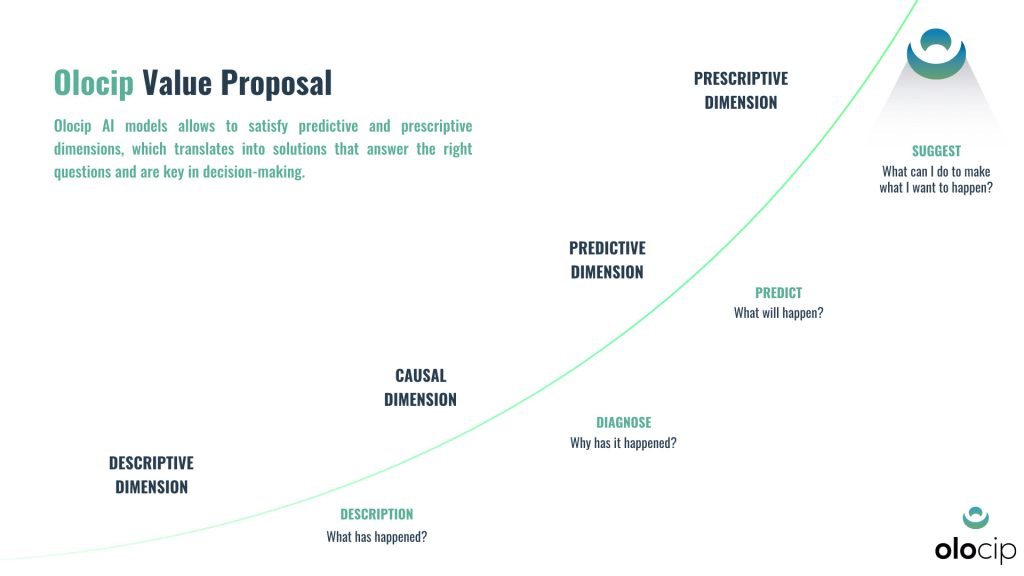

Using IBM’s Watson Knowledge Studio and Watson Natural Language Understanding tools, JAAI’s product automates scouting reports, making them searchable and auto-synthesizing key descriptions and alphanumeric data points for individual players into a single dashboard. The contents of these dashboards then allow players to be easily and quickly ranked, studied and compared against the club’s criteria. This last point is actually extremely important, and is being solved for independently by other tools -- Esteban Granero’s Olocip, for one, has correctly managed to predict that certain high-performing players would, for example, score more goals but provide fewer assists at their new clubs, purely on account of how their traits interact with those of the rest of the team. Their value proposal, pictured below, sheds some light on the way in which they and other similar providers are defining the scope of the problem.

But anyway, the beauty of JAAI SCOUT is in its simplicity -- the qualitative expertise of scouts is preserved as part of the decision making process, but much of the second-degree inefficiency in interpreting it is removed. In fact, perhaps the only novel informational addition that SCOUT makes is the use of social media analytics -- powered by Watson Personality Insights and Watson Analytics for Social Media -- to provide supplementary insights on what a player might be like within the fabric of the dressing room.

This particular product -- as well as a complementary player valuation algorithm, designed to help clubs optimize their negotiating strategy once a target is identified -- has already been used successfully by teams in Germany’s Bundesliga. Meanwhile, similar products, like playmaker.ai (an ‘Analytics-as-a-Service’ offering), and another being developed collaboratively by Loughborough University and Statmetrix, are expected to see wider use -- perhaps even in the English Premier League -- by as soon as the end of 2020.

The week before the match:

Training a team of players is a complex medley of tactics and sports science -- ranging from exertion analytics to personalized nutrition -- but within traditional methods, these two facets are often totally separate. The tactical side of the game is largely, stubbornly free of technological insights, and coaches (like Marcelo Bielsa at Leeds - check this out for a laugh) who favor even superficial techniques like game film review are a minority.

Recently, though, an ecosystem of tools has emerged that might make technologizing the training design process irresistible.

If you’ve ever played FIFA, you’ve experienced the intersection of AI and football. The reality, though, is that a multiplayer game like FIFA has to solve for much more than a trainer does -- its game environment has to account for the parameters and directions of not one but two actors (sides, or players), while also purposefully simulating a degree of ‘randomness’ (which generations of conspiracy theorists have questioned).

A trainer, meanwhile, simply wants to be able to -- at most -- imagine the perfect attacking move against different kinds of defense (wherein defense could be defined as a discrete, finite variable), and then measure how each player’s decision-making in similar situations compares to the ‘ideal’. In other words, they are only interested in optimizing the outcomes of one actor.

Several approaches can help with training players towards this ‘optimum’. Some are purely statistical, offering useful high-level insights purely by analyzing, say, data that wearable devices already collect. And they needn’t even be particularly esoteric.

A 2018 study at Loughborough, for example, plugged 21000 pieces of GPS data from the Chelsea Football Academy into a simple ANOVA analysis; from this alone, they were able draw a number of fascinating conclusions about how quantities of high-speed running differed significantly among players in different positions during actual matches, but did not differ much during training. In other words, they found reason to question basic inefficiencies in the club’s training design; creative center midfielders, for example, were being made to complete disproportionately long runs in training, instead of focusing on more marginally useful positional or tactical work.

Others are far more daring in scope. Acronis, a Russian-Singaporean data storage firm, spent years signing contracts with huge clubs like Arsenal and Liverpool to store their game footage; eventually, though, they realized that they were sitting on a goldmine. Over the past few years, they’ve developed a suite of tools to apply ML techniques to this footage, tracking repeated errors on one of a player’s feet (suggesting a need to train it), lagging stamina (suggesting a need for endurance work), and even the accuracy of passes (suggesting a need to, well, be better).

It’s cool stuff, but the premise is simple, and unlike most real-world manifestations of AI, there is a clear ‘winning outcome’ in sport, whether a completed pass, a goal, or as a weaved combination of several mini-events, a win. Firms like Acronis are merely growing alive to the fact that techniques which work in areas like video games -- where an entire environment has to be created -- can even more easily be applied to evaluating and then remedying first-order outcomes in an environment that already exists. The need for this is best summed up by Serguei Beloussov, Acronis’ founder:

There are some amazing coaches, and there are some less-amazing coaches. Neither great teams nor good teams can afford to only have less-amazing coaches.

The day before the match:

After months of signing and training players, what ultimately matters most is what transpires on a matchday. This is the point at which, historically, coaches have tended to put their hands up and say that they can only control what they put out — to the extent that they can field players of their choice who they have trained as they saw fit — and not necessarily cater that output to who they are playing against.

Here, as elsewhere, the tides are changing. We’ve talked a lot about the statistics that training sessions churn out, and a coach could easily rank their players internally based on those. But if they knew who would hurt a particular opponent the most?

In illustrating these changing tides, we’re going to take a voyage down the English footballing pyramid, where the waters are decidedly humbler. (Please appreciate this accidentally cohesive metaphor).

In 2019, the ever-experimental team over at IBM Watson decided to revamp 7th-tier Leatherhead FC into a fully AI-dependent football club. They built a suite of tools used for general purposes ranging from psychological conditioning, to training, to recruitment, but some of their most intriguing work assisted the club in preparing specifically for each game and each opponent.

Several parts of the Watson suite chipped in. Watson Discovery, for example, enabled Leatherhead to analyze their upcoming opponents on the basis of everything from their past match reports to their social feeds. The result of this analysis would then be a dashboard of key information, covering everything from the styles, temperaments and statistics of the opposition’s most influential players, to insights on which side of the pitch the opposition’s forwards tended to favor most.

Watson Assistant, meanwhile, enabled Leatherhead coaches to easily identify key, intersectional pressure points to review with their players. One example cited in an IBM blog post covers an aspect of the team’s preparation for an upcoming match against Hitchin Town FC. Coaches found, using Assistant and a huge database of footage, a pattern of Leatherhead’s defenders making immature tackles, as well as a tendency for Hitchin’s forwards to fall over easily in the penalty box, in trying to fool the referee. [Clearly, though, they didn’t do enough with this information. Poetically enough, Leatherhead’s left-back conceded a penalty on matchday, Hitchin scored it, and Leatherhead were knocked out of the FA Cup, their most prestigious competition of the season. Whoops.]

What is clear, even if not practically helpful in the backwaters of English football, is the staggering potential of AI like IBM’s to revolutionize the pre-match tactical process -- coaches just have to be willing to admit that they are not omnipotent.

Unfortunately, that particular paradigm shift is harder to evangelize among top coaches, who believe (correctly or otherwise) that their success is owed solely to their sheer footballing intellect. This is especially frustrating because the higher up the footballing pyramid we go, the more infrastructure there is for AI to synergize with -- world-class teams actually have the facilities, equipment and coaching personnel to act properly on hunches, unlike teams like Leatherhead.

I hope (and to be fair, expect) that more top teams will get onboard soon. Because it also merits considering that the more commonplace such applications become at the highest levels of the sport, the more likely it is to be replicated, and thereby become cheaper and more democratically accessible for lesser teams. So the ivory tower can be useful.

Integrity

Amidst all this talk about how to extract the most emphatic gains in performance, there is a need to consider how the essence of the game itself is going to be able to keep pace. The integrity of football comes before anything, and fortunately, the governing bodies which serve as the custodians of this integrity are not (as) stubborn about technology.

Fine margins

The first high-profile introduction of technology into the laws of football came with goal-line tracking. The history of top-tier football is rife with instances of goals that crossed the line and should have counted, and by 2012 or so, the avoidability of such errors was finally acquiesced by lawmakers.

The solution to this already existed, and simply needed to be re-programmed for the dimensions of a football pitch. Sports like cricket (since 2001) and tennis (since 2006) had been using Sony’s Hawk-Eye system for years.

It works quite simply. The system uses up to seven high-performance cameras attached to the roof of a stadium, each positioned to track the ball in play from different angles. A step deeper, these images are then triangulated to produce a three-dimensional perspective on the ball’s trajectory and location. In football, for a goal to count, the entirety of the ball has to cross the goal-line.

So when the Goal-line Decision System (GDS) was introduced to the Premier League in 2013, referees simply began to receive little pulses on their digital watches to indicate that the binary threshold -- crossed or not crossed -- had been satisfied. The simplicity of this binary check meant that referees could decide on whether or not to award a goal almost instantaneously, preserving both the integrity and, crucially, the flow of the game.

Absolute confusion

I cannot say what I think. I will be in trouble, I will be suspended, I don't want to be. I would like to say but I cannot say - Spurs manager Jose Mourinho on VAR

Here's where flow comes to die. Any football fan will see the letters VAR and feel a combination of vitriol, relief and genuine confusion well up within them. Video assistant referees -- essentially, a real person sitting in a remote location watching the match -- were introduced into the laws of the game in 2018, for the purpose of correcting ‘clear and obvious errors’ made by on-field referees amidst the speed and pressure of open play.

Four types of on-field decisions can be reviewed: goal/no goal (checking whether an infraction was made either leading up to or during the scoring of a goal), penalty/no penalty (checking whether an callable infraction was or was not committed), direct red card (checking whether a particular infraction merited the sending off of the player), and mistaken identity (it used to be hysterical when the wrong players would accidentally get sent off, but apparently that’s not good).

The mechanics of the review itself are pretty simple. The remote VAR team checks every decision that could come under one of those categories. If no error has been made by the on-field referee, this validation is communicated to them. In other situations, if a call or lack thereof is dubious, the VAR team can ask the referee to stop play while it is reviewed. At this point, three things can happen: the decision is formally overturned by VAR, the referee is recommended to go to a pitchside monitor and reassess it themselves (pictured below), or the referee is given advice but chooses to ignore it. You can imagine the novel kind of tension that such breaks in play introduce.

In any event, the point of this mention of VAR is not to call into the spotlight any particularly notable technology, but rather to trigger reflection on the cultural and (loosely) ethical aspects of the interaction of technology with sport. The problem with VAR is that it isn’t binary in the way that GDS is -- it merely outsources a human decision to another human in different circumstances of time and pressure. The question then becomes one of the essence of the game -- was sport meant to be played perfectly, even at the cost of flow and drama, or is some kind of imperfection part of why we love it? And does this philosophical question bear considering in other industries and spaces too?

Consumption

If it isn’t already readily apparent, I’m fanatical about this sport. And I’m surrounded by others exactly like me. Football is a massive market, and if not before, then definitely now in its more corporate iteration, it depends almost entirely on people being able to consume it. It thus feels fitting to conclude this article by discussing how generic sales technology is being spiced up to keep this big, money-spinning machine churning.

This reinvention manifests itself in what you might call the ‘traditional’ fan experience -- going to a stadium on matchday and singing your heart out with your club’s most faithful. For big clubs, ticket sales are relatively inelastic. But what about middle- to lower-tier clubs who depend on gate revenues to sustain their operations? Re-enter AI.

One Premier League team has enlisted the aforementioned Acronis to help them make smarter sales decisions -- in terms of pricing, marketing and even merchandising operations, which are influenced by the turnout on matchday. Acronis has helped them develop an experimental algorithm to combine internal data, past ticketing figures and even meteorological predictions, with the aim of forecasting matchday turnouts against different opponents.

This reinvention also manifests in what has become, especially in recent times, the crux of sporting consumption -- televised coverage.

Without wading into the dynamics of the TV industry, which is plagued by fragmentation, contracts of asymmetrical tenures that should be worth less or more, and poor marketing, there is a definite need to produce the best coverage possible. In response to this, studios have pulled out all stops. They’ve begun to teach even veritable football veterans how to navigate and annotate large touch screens instead of discussing matches abstractly. And on a more SaaS side of things, they’ve begun to enlist the likes of AWS and Opta (an incredible statistical platform) to provide real-time insights on matches, via social media as well as via pop-ups within the match displays themselves.

In other words, they’ve begun to covet the same individual and team-level data that coaches want for themselves, albeit for more aesthetic purposes. This is simple more evidence in support of the notion that collecting and making sense of this data is the key to success in football today, whether you’re a coach, club operator or media distributor.

The word ‘aesthetic’ feels like a suitably ironic point to end on, because football today is so much more than a crowd-pleasing sport. With its transition into a massive, lucrative corporate network has come an economically-motivated need to optimize performance, integrity and consumption. That these three pillars sound like they’ve been poached straight from a cybersecurity startup’s website says it all -- in this day and age, the way to optimize, well, anything, is to technologize it to whatever extent is possible. Accordingly, whether technology is helping or hurting the sport at its emotional core is debatable, but its utility -- no, its vitality -- to football in its present form is not.