21st Century GAAP

How do we value a digital company like Facebook or Amazon that has negligible tangible assets?

Peter Drucker, Father of modern management theory, famously stated more than 40 years ago, “You can’t manage what you can’t measure”.

This eventually became the premise on which accounting standards were built upon.

We often methods such as DCF analysis or comparable analysis to value companies or assets that apply to companies selling physical goods, generating stable revenues and predictable cash flow inputs and outputs, assuming to grow in earnings and yielding returns on their fixed assets, but have we ever paused and wondered, how would we do the same for digital companies whose “goods”, if I may, are intangible in nature? How do we value something we can’t touch?

Do we not include this in our valuation, as Peter claims?

Especially in today’s world, the largest companies often create immense value through their intangibles.

“Uber, the world’s largest taxi company, owns no vehicles. Facebook, the world’s most popular media owner, creates no content. Alibaba, the most valuable retailer, has no inventory. And Airbnb, the world’s largest accommodation provider, owns no real estate.”

For some of the biggest technology companies like Amazon and Facebook, the unique combination of their people, their invented systems and processes, and their physical presence create value for the company and their investors, which is exactly why, often, they trade at remarkably high multiples.

For example, take Alphabet (Google’s Parent) who recorded a $1.3 billion operating loss in 2019 on moonshot projects that it classed as “other bets” on its Income Statement. A discernible investor in Alphabet would find it difficult to assess such expenditures and possibly be spooked by the vagueness of this loss.

This trend has in fact become mainstream primarily due to the pivotal role technology has begun to play in our lives, as digital companies steer away from traditional practices of providing physical goods to truly valuable intangible assets such as data, content, software code, brands, inventions, industrial and technical know-how.

This has created a self-fulfilling prophecy, where corporates have caught up with this trend and have started venturing into intangible assets like technology, software, customer relationships, and brand recognition, rather than traditional physical assets, property, plants, and equipment. Customers have ultimately benefitted not only from the increased access to more advanced services but also supporting them with a highly connected and powerful ecosystem, the Internet sphere.

This raises the following question: does the current accounting framework accurately capture the value of these digital companies and the intangible assets that they rely so heavily upon?

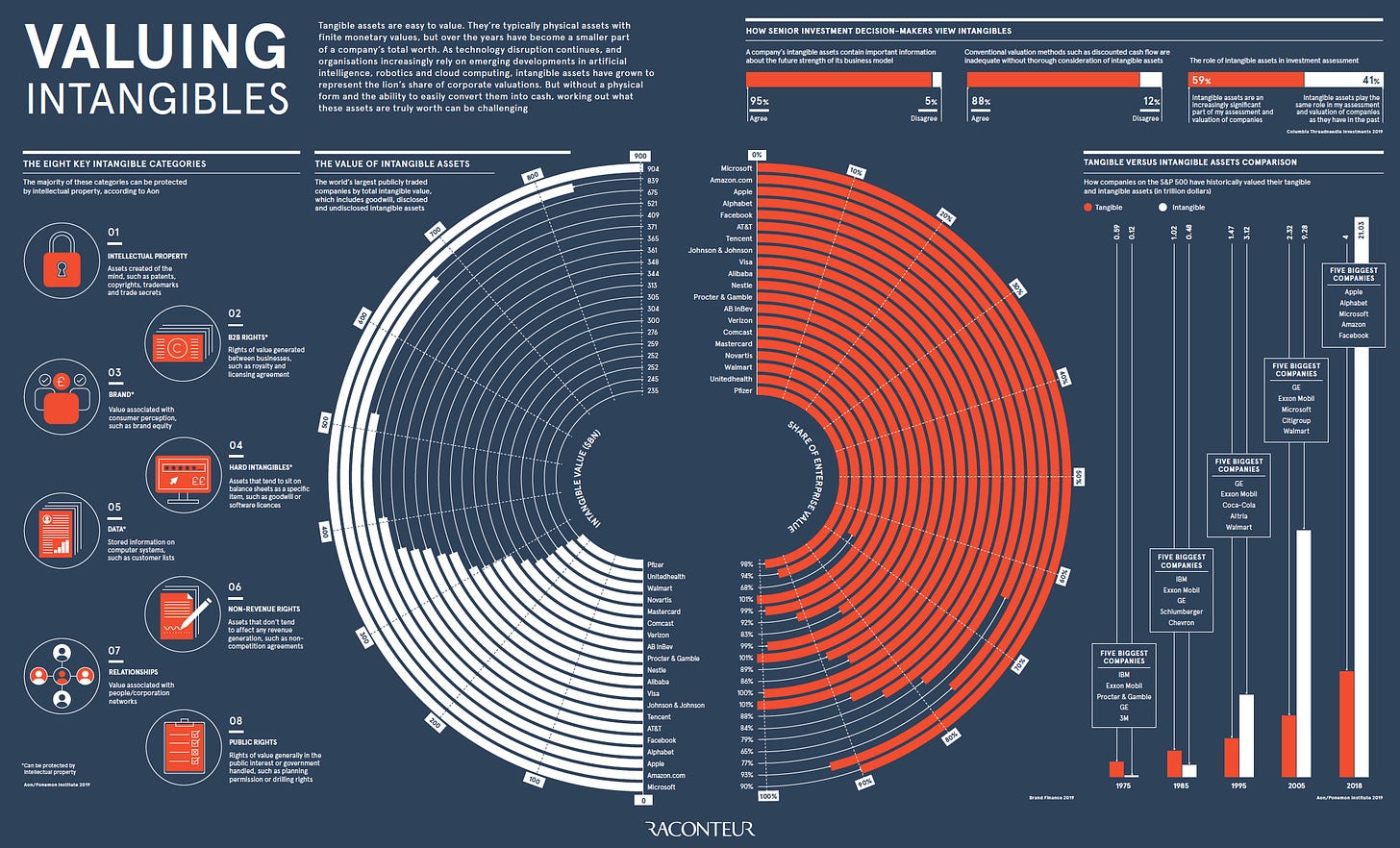

The measurement system, called GAAP - Generally Accepted Accounting Principles, is inherently flawed. In valuing digital companies, there is a huge gap – pun intended (I’m sorry, couldn’t resist) — in GAAP. According to Ocean Tomo, whereas 83% of the market value of the S&P in 1975 comprised companies whose businesses were based on physical or tangible assets, in recent times, that number has fallen to 16%.

And, by the nature of it, it is inappropriate to view R&D, proprietary algorithms and software, as mere operating expense outlets, when these intangibles could actually alter the growth path and the value creation of the company. Moreover, physical assets and digital intangible assets differ fundamentally – while physical assets depreciate and lose value over time with use, intangible assets actually increase with use.

And even, more generally, undisclosed intangibles (calculated as the difference between a company’s market value and book value) cannot be accounted for in the current accounting standards because there simply has been no transaction/revenue source that supports its value. In fact, 34% of the total worth of the world’s publicly traded companies is made up of undisclosed value.

Source: Visual Capitalist (For a higher-quality picture, click here)

Remarkable rise of intangibles–recognizing invisible trillions of dollars

In 2018, intangible assets for S&P 500 companies hit a record value of $21 trillion. In just 43 years, intangibles have evolved from a supporting asset into a very prominent area of consideration, albeit qualitative – today, they make up 84% of all enterprise value on the S&P 500, a massive increase from just 17% in 1975.

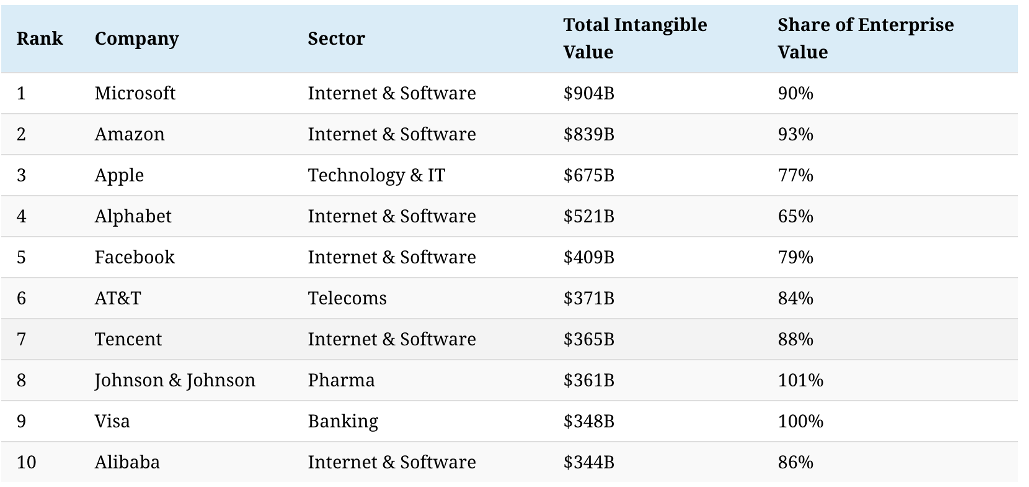

In the table below, the top companies listed and the percentage of EV in Intangible value reflect the emphasis on intangible assets as a springboard for a company’s growth potential:

Outdated Valuation Methods

Why are these assets not accounted for, or invisible?

Intuitively, investments in R&D are driving future growth potential of the company, and yet, balance sheets do not reflect that benefit. In fact, the tech companies we often see in large losses – even the likes of Amazon - in its early stages reflect this exact fallacy.

Often, a portion of intangible assets, acquired through M&A, are measured at fair value, recorded on the balance sheet, and potentially written down – never up – in the case of impairment.

If certain value-driving assets are recognized because they are considered important in the context of an acquisition or business combination, then why are they unimportant while being developed internally?

Although the implied conclusion here suggests that the market values of digital companies should then have no relationship to their book value or to the assets on their balance sheet since they are not reflective of the company’s future cash-flow generating ability, does it really matter?

Even though it makes it evidently harder for us to value companies quantitatively, it also opens up an entirely new arena of possibilities and opportunities for us to look beyond the veil of mystery of the undisclosed, untouchable, yet precious and game-changing, assets.

Those companies that rely on artificial intelligence and proprietary software algorithms with superior customer experience, often leading to more sticky business models, higher retention rates, non-linear growth paths, ultimately benefit from higher income, higher margins, and higher future cash-flow generating ability. And yet, unfortunately, we have no way of reflecting this on the balance sheet for those assets.

Interestingly,

The Nortel bankruptcy filling in 2009 substantiates this gap between the accounting treatment of intangible assets and the actual value in the market perfectly. When Nortel filed for bankruptcy, its physical assets were sold for US $3.2 billion. And its intangible assets, just valued at $31 million on its balance sheet, ultimately sold for a staggering $4.5 billion.

Would Nortel have entered bankruptcy at all if its management spent more time actively managing its intangible assets?

Take, for example, Instagram. When Facebook acquired Instagram in 2012, it was 20 months old, had virtually no revenue, effectively no assets, and 12 employees. If we valued Instagram using a DCF, the company would have been worth $0. Yet, Facebook acquired it for US $1 billion, reflecting Facebook’s perspective on the true potential in Instagram’s intangible assets. And today, Bloomberg Intelligence estimates that Instagram standalone would be worth more than US $100 billion.

But then, what makes it really hard to value intangible assets accurately?

Why have they not included this in accounting standards already?

If we take a cost-based approach, the problem is, there is effectively no correlation between the cost and the potential value of an intangible asset. Firstly, there is no indication to what extent the intangible asset will impact future cash-flow generating ability and growth potential, and secondly, the value of the intangible asset is unknown – you can spend $10M on R&D and get nothing, and even spend $100K on R&D and develop intangible assets worth billions. Even when we consider the Net Present value (NPV) approach, the discounting rate cannot be determined since we can be reasonably sure that the future will not reflect the past or current situation when it comes to intangible assets.

Let’s consider the other traditional method – comparables. Valuing intangible assets through this method is fraught since intangibles are unique, differentiated, and have varying returns on investment, and thus, a benchmark or performing comparisons is challenging.

How are companies accounting for these potentially key value drivers?

Companies are now disclosing new non-GAAP types of key performance indicators (KPIs) or metrics – Daily / Monthly Active Users (DAUs / MAUs), Average Revenue per User (ARPU), customer acquisition costs and churn rates, percentage of recurring revenue, etc.

However, a potential drawback to this could be the calculation of these metrics, since they are non-GAAP and do not have strict guidelines on its calculation, every company has its own freedom to decide how much to disclose, and what to include/exclude in every calculation.

Reflecting investors’ sentiment of the calculation of these metrics,

“The general perception is that the inputs may be unreliable, and therefore the output is unreliable. But that’s not an excuse to ignore something that is a key value driver for the company, some estimate is better than no estimate.” – Glen Kernick, MD and Tech industry lead at Duff & Phelps Corporation, a global corporate finance advisor.

With these fallacies and gaps in the potential valuation of digital-asset-heavy companies, not only do we need to update the 50-year-old GICS and GAAP accounting measures, but we also need to urge companies to mold their reporting to include more non-GAAP metrics and qualitatively mention its intangibles.

There are various organizations attempting to create methods that fill the gap with traditional accounting methods.

The International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) is encouraging companies to tell a coherent long-term value-creation story and focus on various types of capital that are material for them. IIRC identifies six types of capital: financial, manufactured, intellectual, human, social and relationship, and natural. Together, they represent stores of value that form the basis of an organization’s value creation and are reasonable qualitative judgments on any explicitly undisclosed or disclosed intangibles.

There are several other methods as well for companies to explicitly disclose truly valuable intangible assets:

Detailed segregation of the areas where the operating expenses are spent.

Potentially future areas of growth and their predicted cashflows-generating ability.

Conclusion

Just a few thoughts:

What would a willing buyer pay to employ the intangible asset?

What is the expected return on this intangible asset?

What is the useful life of this asset?

What portion of the operating income does this generate?

The amorphous term, “goodwill”, often used to capture these aspects, needs to be expanded and broken down to include all types of intangible assets. The fundamental principle on which accounting lies – Matching principle, wherein the expenses need to be reported in the same period as when the related revenues are earned – needs to be slightly altered to ensure intangible assets (since they essentially yield benefits from these assets in the future) are adequately accounted for in the present valuation of a company.

Historical data has also supported the sizeable future return on intangible assets through popular spends such as R&D investments – across countries and companies, there has been evidence of a correlation between R&D and Return on Assets and future performance.

It is time for us to change the 50-year old accounting standards to comprehensively value the new-age companies, which have become increasingly digital.

For now though, as a reminder, do not discount the importance of intangibles. Those who thought that Facebook and Amazon in their early stages were trading at obnoxiously high multiples, including me, well, they (we) need to adapt to the new valuation age.

For anyone interested in knowing more about research on methods attempting to evaluate intangible assets:

Sources

Knowledge @ Wharton, University of Pennsylvania

I'm sorry but new era thinking has never ever worked. See 1928, see 2000. Yes assets can be valued differently, earnings however not. A dollar earned is a dollar earned. Free cash flow is still a very good metric.